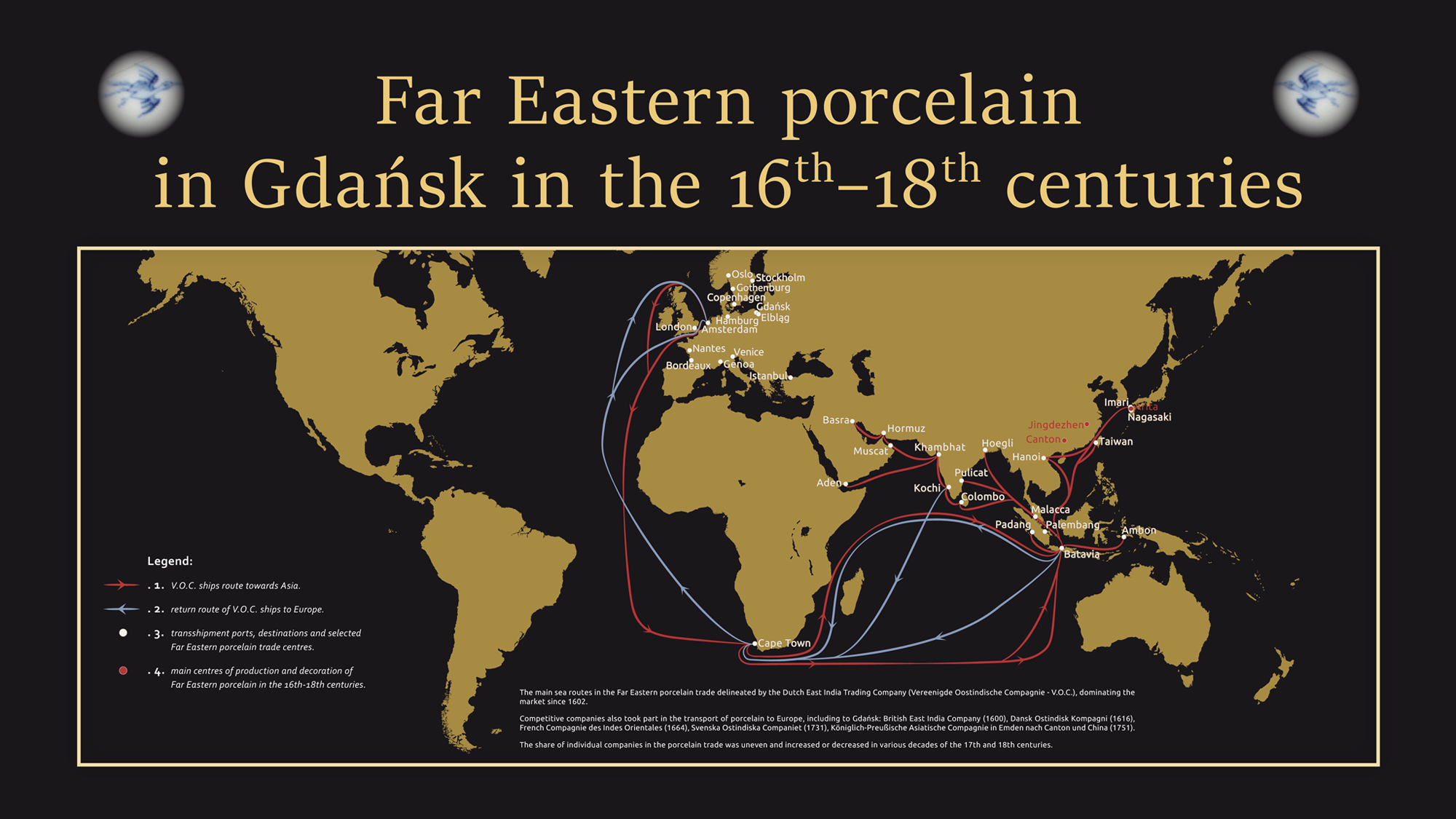

Legend:

- V.O.C. ships route towards Asia.

- return route of V.O.C. ships to Europe.

- transshipment ports, destinations and selected Far Eastern porcelain trade centres.

- main centres of production and decoration of Far Eastern porcelain in the 16th-18th centuries.

The main sea routes in the Far Eastern porcelain trade delineated by the Dutch East India Trading Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie – V.O.C.), dominating the market since 1602.

Competitive companies also took part in the transport of porcelain to Europe, including to Gdańsk: British East India Company (1600), Dansk Ostindisk Kompagni (1616), French Compagnie des Indes Orientales (1664), Svenska Ostindiska Companiet (1731), Königlich-Preußische Asiatische Compagnie in Emden nach Canton und China (1751).

The share of individual companies in the porcelain trade was uneven and increased or decreased in various decades of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Chinese porcelain in Gdańsk

Based on excavations carried out in the historic city of Gdańsk, it can be concluded that Chinese export porcelain appeared in the houses of Gdańsk townspeople. The earliest objects date back to the second half of the 16th century. The presence of porcelain increased steadily throughout the 17th century, reaching its culmination in the 18th century. These were mainly tableware. In the 17th century, large plates and bowls (eagerly imitated in Dutch faience factories), while in the 18th century, with a change in customs, small cups and saucers for drinking colonial beverages (coffee, tea and chocolate) as well as large plates and bowls tableware. Depending on the wealth of the houses, they contained objects decorated with various decoration techniques. The cheapest were massive saucers and cups decorated with underglaze cobalt, and later the so-called Imari style, the most valuable are thin-walled objects decorated with overglaze paints and enamels as well as gilded. Only in a few locations the presence of thin-walled, early Japanese porcelain was found.

What is ‘export porcelain’

The objects in the display cabinet nearby are the so-called export porcelain specimens. They differ significantly from products formerly manufactured in Asia for domestic use. Items similar to those whose production began in the 16th century for shipment to Europe and, from the 18th century, also to both Americas, were not and usually still are not found in Chinese or Japanese homes. They differed in shape and use. Their cultural connotations were also different.

Europeans arriving to China from the 16th century took an active role in the process of creating pottery intended for export and sale on the Old Continent. Their suggestions concerned both the shapes of the ordered vessels (silver or wooden models of items unknown in China were brought), decoration patterns, and also included the enrichment and modernization of production. The Jesuits, who were well-received at the imperial court, played a special role in this process. They acquainted Chinese artists with European canons of beauty (in particular the art of perspective and drawing) and introduced certain technical innovations, thus enriching the native repertoire of means of expression. All this made export porcelain a new genre, created in the meeting of two cultures and fascinating connoisseurs.

Development of export porcelain production in China

The history of Chinese porcelain production intended for export both to Asian countries and other continents dates back to the European Middle Ages. The first mass-produced specimens decorated with delicate, blue-greenish glaze in various shades, called celadons (Chinese: 青瓷 qingci), were produced especially for export as early as in the 13th century, becoming determinants of the canons of beauty and taste in ancient Japan, Korea and Vietnam. However, as late as in the Ming 明朝 dynasty period (1368–1644) this process intensified (mainly thanks to the development of export production to Muslim countries), and in the 18th century it led to the creation of the first mass production in the history of the world, where the same porcelain models were made in tens or even hundreds of thousands of pieces. Initially, they were only found in royal and magnate courts – and from the end of the 17th century they also appeared in wealthy burgher houses. Depending on the social position of their owners, there were different types of objects on the tables. In Muslim countries and in Europe, to pottery vessels were sometimes added metal fittings or inlaid decorations, thus adapting Chinese forms to local needs.

Trade campaigns and transport to Europe

Initially, in small quantities, Chinese porcelain reached royal and princely courts in Europe by land, via the so-called the Silk Road. The first vessels painted with underglaze cobalt were also brought along the same route. With the expansion of Europeans, preceded by a series of important geographical discoveries that allowed for the creation of new routes, maritime trade routes were created, along which many different goods were transported: spices, coffee, tea, cotton, ores and handicrafts, etc.

The Empire of China – defining itself as the ‘Middle Kingdom’ – as well as the Empire of Japan in the so-called in modern times, practiced a policy of isolation. For this reason, the mere possibility of arriving at one of the ports was problematic and required great diplomatic efforts. In the case of both countries important for the production of export porcelain, the Jesuits became the first intermediaries in both political and commercial negotiations. They gained a much better and stable position at the imperial court of the Ming dynasty. Thanks to their support, the Portuguese were the first to receive the imperial privilege and monopoly on the Chinese porcelain trade. Already in the 16th century, extensive production of porcelain intended for the European market began, with patterns set jointly by Portuguese merchants – the emperor’s protégés – and Chinese craftsmen. These items arrived in Europe on ships called carraca. Hence, when Dutch merchants took over this trade through armed actions and violence, the later name was created to describe the specific style of export porcelain developed at that time, called kraak. Dutch domination in the porcelain trade lasted for almost two centuries and culminated in the so-called East India Trading Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), abbreviated from the Dutch name V.O.C. It had been operating since 1602 and was involved in trading all kinds of colonial goods – transporting them both on the way to Asia and on the way back, also between Asian ports, from which it made unimaginable profits. An important transhipment port outside Europe was Batavia (today’s capital of Indonesia, Jakarta). Hence, some types of Chinese porcelain, prepared especially for V.O.C., are still called ‘Batavian porcelain’.

Based on the analysis of the obtained archaeological material, it can be concluded that the types of Far Eastern ceramics present in Gdańsk were transported to Europe in connection with the activities of various trading companies that also periodically had a significant share in the trade in Far Eastern porcelain: the British East India Company (1600), the Dutch Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (1602), Dansk Ostindisk Kompagni (1616), the French Compagnie des Indes Orientales (1664), Svenska Ostindiska Companiet (1731), Königlich-Preußische Asiatische Compagnie in Emden nach Canton und China (1751). The share of individual companies in the area in question was uneven and increased or disappeared in various decades of the 17th and 18th centuries, with the largest one undoubtedly being attributed to the Dutch Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (V.O.C.).

The history of the porcelain trade was determined by political changes. Due to violent political struggles in China, which resulted in the change of the Ming to Qing dynasty, in the 17th century Japanese products temporarily replaced Chinese porcelain on the European market. Also in this case, the Dutch maintained the monopoly until the end of the 18th century. After the new dynasty was stabilized, production in the Jingdezhen imperial ceramics centre was rebuilt, and during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1661–1722) it reached an extremely high technological level. Japanese porcelain continued to constitute a steadily increasing percentage of world production exported to Europe. However, it was much lower, both because of the local organization of production and its costs, which were higher than those that the Empire of China could offer. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, after the fashion for Japonism appeared, it was already significant, which is also confirmed by the archaeological material obtained in Gdańsk.